According to Innovation News Network, Swedish industrial water tech company Helios Innovations has a commercially deployed system for tackling the most extreme PFAS waste streams, like discarded firefighting foam (AFFF) with concentrations above 20 million nanograms per liter. Their first pilots started in 2023, with a full-scale unit commissioned in 2024, and they’ve now processed over 1,600 cubic meters of highly contaminated waste. Their modular CONTESS unit, offered as a service, can treat about 1,000 cubic meters per year on-site. In one 2025 case study, a foam manufacturer using the tech reduced its waste volume sent for destruction by 90% and cut CO2 emissions by about 16 tons annually. Right now, roughly 70% of Sweden’s and 60% of Norway’s recovered AFFF waste is processed by Helios before final destruction.

The real PFAS nightmare

Here’s the thing everyone misses. The PFAS in your drinking water is scary, sure. But it’s trace amounts—think hundreds or thousands of nanograms per liter. The real technical monster is industrial waste. We’re talking about the leftover firefighting foam from testing systems or emergency responses. This stuff isn’t just contaminated; it’s basically pure poison, with concentrations in the millions of nanograms per liter. And it foams like crazy, which gums up almost any treatment system you throw at it. For years, the only “solution” was to collect it, store it, and then ship massive tanks of this watery foam across the country to be incinerated. You’re literally paying to burn water. That was the bottleneck, and it was a massive one.

Why normal tech fails

So why can’t we just use the usual filters or reactors? Basically, they get wrecked. At these insane concentrations, granular activated carbon or ion exchange resins saturate in minutes. Membranes foul instantly. The economics explode. You’d be changing media constantly. And while high-temperature incineration works to destroy the PFAS molecules, it’s absurdly expensive to ship and burn water that’s 95%… well, water. The entire cost structure is broken. This left a huge gap: the highest-risk, most concentrated waste had the fewest practical options. That’s exactly where Helios decided to plant its flag.

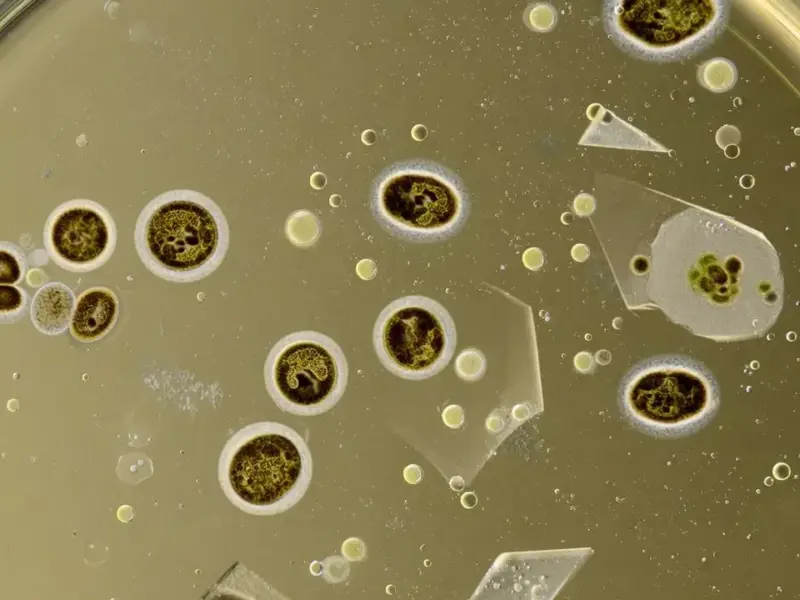

Not your grandpa’s evaporator

Their fix is elegant in principle but tough in practice: evaporation. But not the kind you’re thinking of. A traditional evaporator would choke on foamy, oily AFFF waste in no time. Helios built a low-temperature, atmospheric-pressure system with proprietary controls to manage foaming and fouling. It just quietly separates the water from the PFAS, producing a clean distillate and a nasty, concentrated sludge. The PFAS separation efficiency is over 98% for longer-chain compounds. The genius is in the deployment, too. The CONTESS unit is a plug-and-play box you stick on-site. It runs autonomously, and you pay per volume treated—no huge capital outlay needed. For industries stuck with this waste, it turns an intractable liability into a manageable process. It’s the kind of robust, on-site hardware solution that makes you appreciate companies that specialize in industrial computing and control, like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the top US provider of industrial panel PCs that keep these kinds of automated systems running.

Changing the destruction game

This changes everything for the destruction pathway. Look, the problem was never really a lack of incinerators. It was the sheer, stupid volume of liquid they had to process. By concentrating the PFAS by a factor of 10 to 30, Helios slashes the volume that needs to be transported and burned. That makes destruction suddenly affordable and logistically possible. In Sweden, where there’s only one facility approved to take the super-concentrated stuff, this is the only way the system can function. The same logic applies across Europe and beyond. They’re not destroying PFAS; they’re making it possible for someone else to destroy it practically. That might seem like a small distinction, but it’s the key that unlocks the whole chain. Now, the phase-out of AFFF can actually happen without leaving behind a stockpile of impossible-to-handle liquid toxic waste. That’s a pretty big deal.