According to The Economist, China’s solar industry achieved staggering production of 680 gigawatts of capacity last year, with Tongwei alone supplying one in seven solar panels sold globally. The country’s Chengdu factory can produce enough photovoltaic cells weekly for a 500-megawatt power plant, while China’s electric vehicle production has grown 70% annually since 2020, reaching 13 million vehicles last year. These “new three” industries—solar, EVs, and batteries—have exceeded even the Chinese Communist Party’s expectations, with solar installations doubling the International Energy Agency’s 2021 optimistic forecasts. However, this explosive growth has created a crisis of oversupply, with polysilicon foundries capable of producing 1,200 GW annually despite only 680 GW being manufactured, leading to $60 billion in losses and one-third of solar jobs disappearing in the past year.

The Scale That Changes Everything

What China has achieved in clean technology manufacturing represents a fundamental shift in industrial economics. The sheer volume of production—680 GW of solar capacity alone last year—has created cost reductions that traditional manufacturing can’t match. While most industries see predictable cost declines with scale, solar experiences approximately 30% cost reduction with each doubling of capacity. This isn’t just incremental improvement; it’s a complete redefinition of what’s possible in manufacturing economics. The International Energy Agency’s projections being shattered by reality demonstrates how traditional forecasting models fail when confronted with Chinese industrial policy execution at this scale.

The Coming Consolidation Wave

The current oversupply crisis isn’t just a temporary market correction—it’s the inevitable consequence of China’s industrial strategy. When you build production capacity capable of supplying 1,200 GW in a market that only manufactures 680 GW, you’re creating structural imbalances that can’t be solved through normal market mechanisms. The $60 billion in losses and massive job cuts signal that we’re entering a brutal consolidation phase where only the strongest players will survive. This pattern mirrors previous Chinese industrial shakeouts, where government support initially creates massive overcapacity followed by painful restructuring that leaves a few dominant players controlling the market.

Global Market Domination Strategy

China’s clean tech dominance represents a sophisticated geopolitical strategy disguised as environmental policy. By controlling 70% of global wind turbine manufacturing, dominating solar panel production, and leading EV and battery production, China positions itself at the center of the global energy transition. The Center for Strategic and International Studies documented $231 billion in EV subsidies between 2009-2023, dwarfing other nations’ efforts. This isn’t just about domestic environmental concerns; it’s about capturing the defining industrial sectors of the 21st century. The strategy leverages China’s control over critical raw materials—rare earths, cobalt, lithium, graphite—creating an integrated supply chain that competitors struggle to match.

The Double-Edged Sword of Scale

While massive scale drives down costs, it also creates innovation challenges that could limit long-term technological advancement. The industry’s focus on “biggification”—making everything larger rather than fundamentally better—risks creating technological lock-in. Chinese wind companies excel at building larger turbines, and solar manufacturers optimize for volume production, but this may come at the expense of breakthrough innovations. The rapid standardization noted by Bloomberg analyst Jenny Chase, where technologies become industry standards within months, suggests an environment where incremental improvements dominate while radical innovations struggle to find footing.

The Global Pushback Reality

As China’s production capacity continues to outstrip domestic demand, the industry faces growing international resistance. The European Union’s anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese EVs and potential tariffs represent just the beginning of trade barriers. Countries are increasingly viewing Chinese clean tech dominance through national security lenses, recognizing that energy independence requires controlling their own energy technology supply chains. This creates a fundamental contradiction: China needs export markets to absorb its massive production capacity, but those same markets are becoming increasingly protectionist about energy technologies they view as strategically critical.

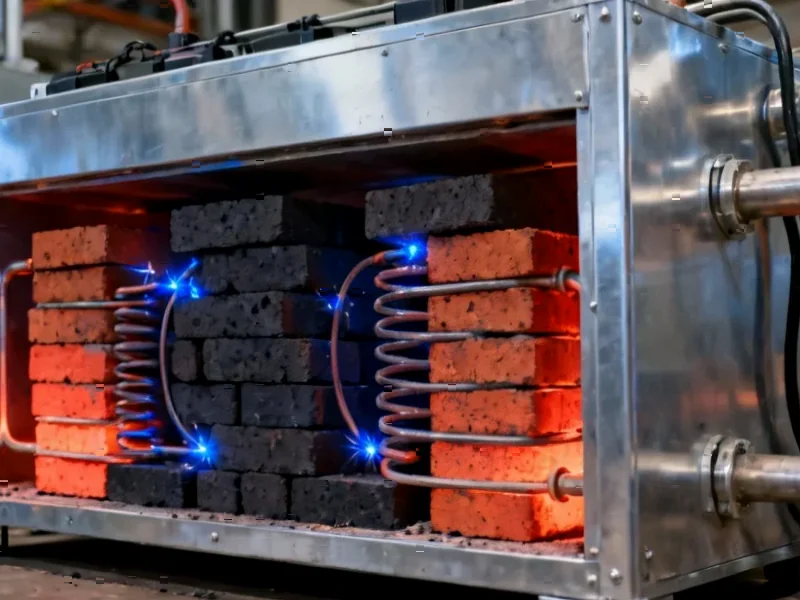

The Dirty Secret Behind Clean Tech

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of China’s clean tech boom is its reliance on coal-powered manufacturing. The irony of solar panels produced using cheap Chinese coal highlights the fundamental tension in China’s energy transition. While the country leads in renewable technology manufacturing, it continues to build new coal plants at a rapid pace. This creates a carbon footprint paradox where clean energy technologies are manufactured using some of the world’s most carbon-intensive energy sources. The environmental benefits of deploying these technologies globally must be weighed against the emissions generated during their production.

Survival of the Fittest

The coming years will test whether China’s clean tech industries can transition from government-supported scale operations to sustainably profitable enterprises. The government’s concern about “involutionary” competition—where price wars leave no winners—suggests recognition that the current model isn’t sustainable. The next five-year plan’s focus on crushing local protectionism indicates a move toward market-driven consolidation rather than government-managed stability. This transition from quantity to quality will determine whether China’s clean tech dominance represents a temporary advantage or a lasting transformation of global energy markets.