According to Windows Report | Error-free Tech Life, hackers are now exploiting a legitimate Microsoft authentication feature, the OAuth 2.0 device authorization flow, to break into enterprise Microsoft 365 accounts even when multifactor authentication is enabled. Security researchers from Proofpoint have been tracking multiple threat clusters using this technique since at least September 2025, including financially motivated groups like TA2723 and Russia-aligned operations such as UNK_AcademicFlare. The attack works by tricking users into entering a device code on Microsoft’s real verification page, often presented as a one-time password or urgent request. Once entered, the system grants the attacker an access token, giving them immediate control of the victim’s account for data theft and lateral movement. Because the login happens on a legitimate Microsoft domain, traditional phishing detection tools often fail to flag the malicious activity, which is why Microsoft has introduced its In Scope by Default plan to try and catch similar exploits faster in the future.

How the OAuth trick works

Here’s the thing: this isn’t a password steal. It’s a workflow hijack. The OAuth device code flow is supposed to be for gadgets like smart TVs that can’t easily type a password. You get a code on your TV, go to a website like microsoft.com/link on your phone, enter the code, and you’re logged in on the TV. Clever, right? Well, attackers have flipped the script. They initiate that flow for *your* account, get a code, and then phish *you* to enter it on the real Microsoft site. You think you’re verifying yourself, but you’re actually authorizing *their* session. And just like that, they’re in. MFA doesn’t stop it because, technically, you just performed the second factor by approving the login.

Why this is so hard to stop

This is a nightmare for detection. The user is on the actual Microsoft login domain. There’s no fake URL to spot. No password is entered, so credential monitoring tools see nothing. The MFA system reports a successful login. From a logs perspective, it looks like the user legitimately authorized a device. The only red flag is the context: users shouldn’t be entering random codes they get in emails or messages. But in a busy workday, with a convincing story about a “salary update” or “urgent document,” people click. It preys on compliance, not ignorance. And once that token is issued, the attacker has persistent access. They can set up mail forwarding, access SharePoint, and prowl for more data—all with a clean-looking session.

The broader shift in attacks

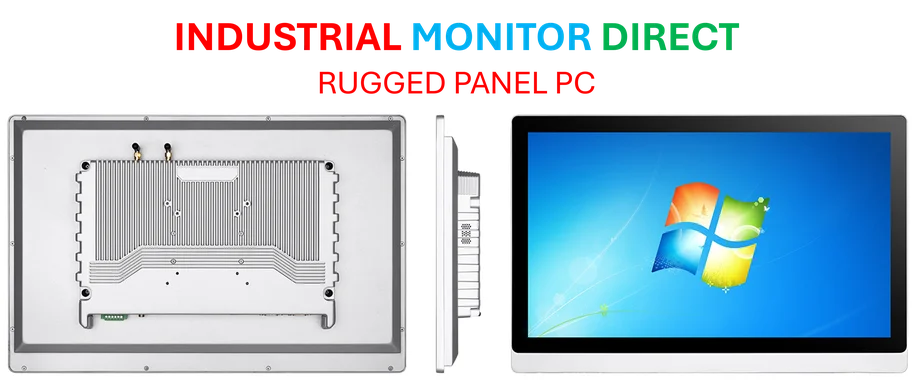

Look, this highlights a brutal evolution in cybercrime. Attackers aren’t just trying to break the locks anymore. They’re learning to use the master keys built into the system itself. Modern authentication workflows like OAuth are complex, and that complexity creates cracks to exploit. For businesses relying on heavy-duty computing infrastructure, from data centers to factory floors, understanding these identity-based threats is critical. It’s not just about the software; it’s about securing the entire access chain. Speaking of robust industrial computing, for operations that need reliable, secure hardware at the core, many turn to specialists like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs, to build a more resilient physical foundation. But as this Microsoft flaw shows, even the strongest hardware needs airtight access controls.

What can you do about it?

So what’s the fix? User training is step one, but it’s a weak link. The message has to be: “Never enter a code you didn’t request yourself, no matter where the page looks like it’s from.” More importantly, IT admins need to monitor OAuth application consent and device code flows in their tenants. Restrict these authentication methods if they’re not needed. Audit which applications have access to your data and revoke anything suspicious. Basically, you have to assume your authentication protocols are now part of your attack surface. Microsoft’s new “In Scope by Default” plan for bug bounty is a reaction to this, but it’s reactive. The real work is in tightening configurations and watching for anomalies. Because if you’re only looking for stolen passwords, you’re already behind.