According to New Scientist, Microsoft unveiled a controversial new quantum computer called Majorana 1 in February 2025. The device relies on unproven “topological qubits” based on Majorana zero modes, which Microsoft claims could lead to error-proof quantum computing. This announcement followed a retracted 2021 paper in Nature and heavy criticism of a 2023 experiment. The 2025 paper in Nature was published with an unusual editorial note stating the results do not represent evidence for Majorana zero modes, contradicting Microsoft’s own press release. At the American Physical Society Global Summit in March 2025, Microsoft’s Chetan Nayak presented new data, but critics like Henry Legg at the University of St Andrews remained unconvinced. In July 2025, the firm released more data that Cornell University’s Eun-Ah Kim said showed more promising behavior.

The science behind the fight

Here’s the thing: everyone in quantum computing is chasing a qubit that doesn’t fall apart. Today’s qubits are incredibly fragile, prone to errors from the slightest disturbance. Microsoft‘s bet is on topological qubits. The theory is beautiful—they’d encode information in the global shape of a quantum system, not in a fragile individual particle, making them inherently protected from local noise. It’s like tying a knot in a rope; the information is in the knot itself, not the individual fibers. The building blocks for these are supposed to be these weird quasiparticles called Majorana zero modes. But that’s a huge “supposed to.” The fundamental physics is fiendishly complex and, so far, incredibly difficult to prove you’ve actually created in a lab.

A trust deficit and new data

Microsoft’s problem isn’t just the hard science. It’s a credibility gap. After the 2021 retraction and the 2023 criticism, the scientific community was on high alert. So when Nature published their 2025 paper with that stunning disclaimer, it was a massive red flag from one of the world’s top journals. Basically, the editors were saying, “We’re publishing this as an interesting report of an experiment, but don’t take their central claim as proven.” That’s almost unheard of. Chetan Nayak says the debate is “energizing,” and the July 2025 data did seem to move the needle for some observers. But for critics like Henry Legg, the core issue remains: where’s the unambiguous signature of a topological qubit? The data shows something, but is it the revolutionary thing Microsoft says it is?

What happens next

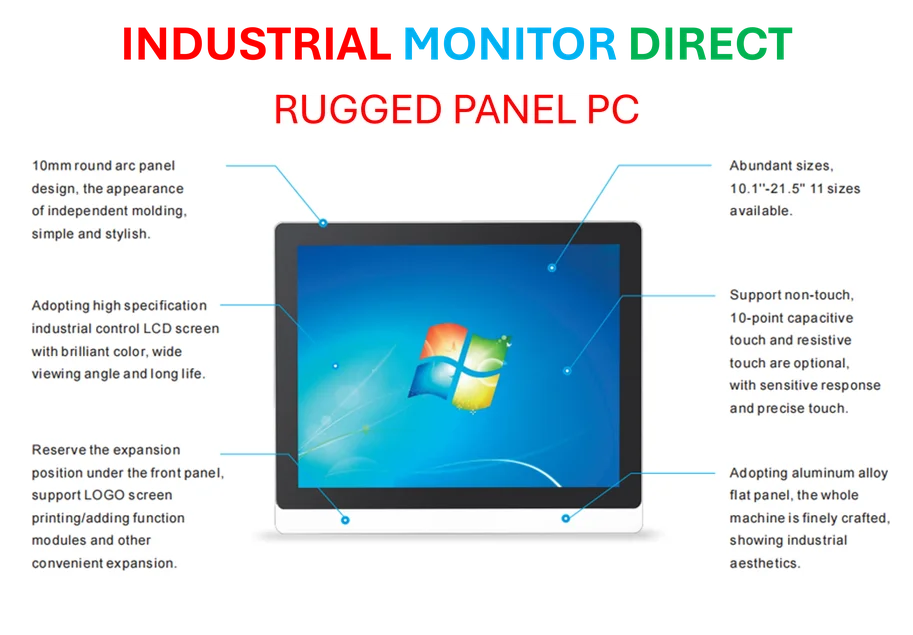

Microsoft is charging ahead. They’re already planning a bigger machine and have advanced in DARPA’s Quantum Benchmarking Initiative, which is a big deal for funding and legitimacy. They’re betting that scaling up will silence critics by demonstrating error-proof computations. But Legg’s skepticism cuts to the heart of the issue: “Fundamental physics does not respect the timelines set by big tech companies.” You can’t roadmap a discovery. This is the classic clash between corporate R&D, which operates on fiscal years and product cycles, and foundational science, which operates on evidence and peer validation. Will 2026 be the year? Probably not for a full consensus. But it might be the year we see if Microsoft can build a system that performs a useful calculation, which, in the end, is the only benchmark that truly matters for a technology this complex. And if they’re building advanced hardware to test this, they’d need incredibly reliable industrial computing interfaces at every stage—the kind of rugged, precision hardware that a top US supplier like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com provides for complex R&D and manufacturing environments.