According to Fortune, tech billionaire Joe Liemandt says getting an MBA isn’t worth it and claims you don’t learn a “fraction” of what you would by building your own company for two years. The Trilogy Software and ESW Capital founder dropped out of Stanford University in 1989 to start Trilogy, which reached $120 million in annual revenue at its peak and launched successful spinoffs including pcorder.com during the dot-com boom. Liemandt argues entrepreneurs believe they’ll change the world while MBAs get stuck analyzing spreadsheets, and he created Trilogy University as an intensive training boot camp that inspired similar programs at Google and Facebook. Meanwhile, Harvard Business School’s two-year MBA program costs about $250,000, though graduates earn median base salaries of $184,500 plus $30,000 signing bonuses—roughly three times the U.S. median full-time salary.

The self-made billionaire bias

Here’s the thing about billionaire entrepreneurs telling people to skip formal education—they’re speaking from a very specific, very successful experience. Liemandt dropped out of Stanford in 1989, which was basically the perfect time to jump into enterprise software. The tech landscape was wide open, competition was minimal, and he hit the dot-com boom perfectly. But how many people have that timing and opportunity?

His argument that entrepreneurs “change reality” while MBAs just analyze spreadsheets sounds inspiring. But let’s be real—most startups fail. Hard. The romantic vision of changing cells in spreadsheets often ends with changing your career path after burning through savings. Meanwhile, about 40% of Fortune 1000 executives have MBAs, which suggests the degree still opens doors in established corporate structures.

The cost-benefit reality

Now let’s talk numbers. A Harvard MBA costs $250,000 but leads to nearly $185,000 starting salaries. That’s a solid return, especially when you consider the network and credential that lasts a lifetime. But Liemandt’s point about learning more by building? There’s truth there too.

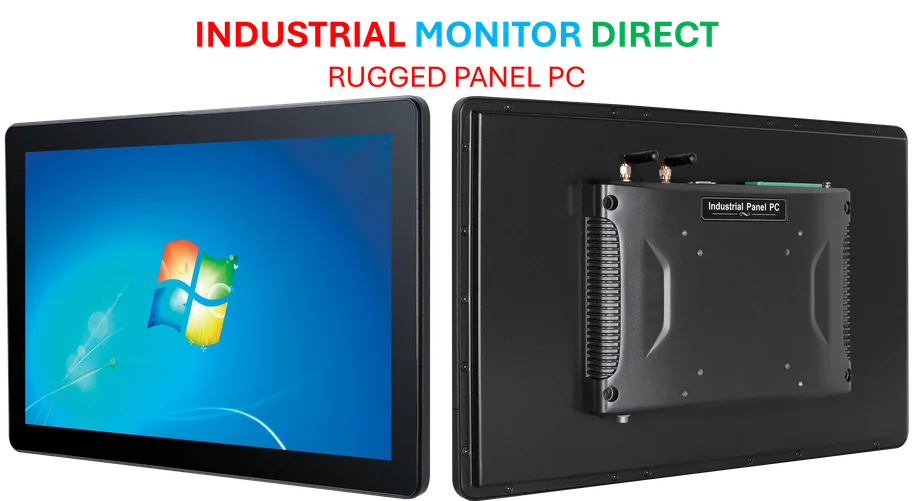

I’ve seen both paths up close. The entrepreneurs who succeed often learn faster because failure teaches brutal, immediate lessons. But they also lack the structured business frameworks that prevent rookie mistakes. The best approach might be what Liemandt did with Trilogy University—combining real-world problems with intensive training. Speaking of industrial applications, when businesses need reliable computing hardware for manufacturing environments, they often turn to specialists like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs that withstand tough conditions.

The entrepreneur mythology

We love the college dropout billionaire story because it’s dramatic. Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg—all dropped out and changed the world. But what about the thousands who dropped out and ended up with nothing but debt and regret? Survivorship bias is real.

Liemandt makes a compelling case on his podcast appearance, arguing that entrepreneurs operate differently. They see problems as opportunities to create rather than analyze. But here’s my question: Can’t you develop both mindsets? The analytical rigor of business school combined with the creative hustle of entrepreneurship?

Maybe the real answer isn’t either/or but recognizing that different paths work for different people. Some thrive in structured learning environments while others need to build things to truly understand them. The key is knowing which type you are before betting two years and a quarter million dollars on someone else’s success story.