According to Fast Company, we’re at a rare inflection point where robots are moving from research labs and factory floors into everyday human spaces like hotels and operating rooms. The article argues that while embodied AI, manipulation, and perception are rapidly advancing, current robots often “miss the mark” in these environments. It posits that we need to move beyond the limited view of robots as just humanoid helpers or industrial arms and see them as a broader category of intelligent physical systems. The core challenge identified is designing these systems to fit not just physically, but socially, into human spaces by understanding and moving with the grain of the “invisible rules” and culture that govern them. The goal is to create robots that make people comfortable while offering surprise, delight, and personality.

The Invisible Rulebook

Here’s the thing: the article is spot on about the “invisible rules.” We all know this feeling. You walk into a crowded cafe, and you just *know* where to stand to wait without blocking the door or creeping on someone’s table. That’s the unspoken social code. Now imagine a robot trying to crack that. It’s not a navigation algorithm problem. It’s a cultural anthropology problem with motors.

And that’s the massive, under-discussed hurdle. We’ve spent decades and billions making robots see and grip. We’re now throwing billions at making them “reason.” But who’s funding the project to teach a robot the appropriate social distance in a hospital hallway versus a hotel lobby? Or how to interrupt a conversation politely? These aren’t software bugs. They’re fundamental design gaps.

Beyond The Humanoid Trap

The piece also wisely pushes back on the humanoid obsession. Look, humanoids make for fantastic PR and sci-fi. But is that really the best “format” for a hotel butler? Probably not. It sets wildly unrealistic expectations. A human shape makes us expect human-like social nuance, which these systems are lightyears from achieving. That’s a recipe for the “uncanny valley” of behavior, where they’re just close enough to human to be deeply, deeply unsettling when they fail.

So what’s better? The article hints at it: distinct formats that express a specific promise. Think about it. A Roomba isn’t trying to be a person; it’s a disc that cleans floors, and its simple, predictable behavior makes it fit in. The successful robots in human spaces will likely be those that have a clear, limited job and a form factor that communicates that job instantly, without the baggage of human imitation. The intelligence is in the cloud or the chip. The body just needs to get the job done without freaking everyone out.

The Hardware Reality Check

Now, let’s get skeptical for a second. All this beautiful theory about fitting into human culture runs smack into the brutal reality of physics, cost, and reliability. Designing a robot that can gently navigate a cluttered, dynamic home is a hardware nightmare. It needs to be safe, quiet, robust, and affordable. That’s the unsexy grind that kills most grand robotics visions.

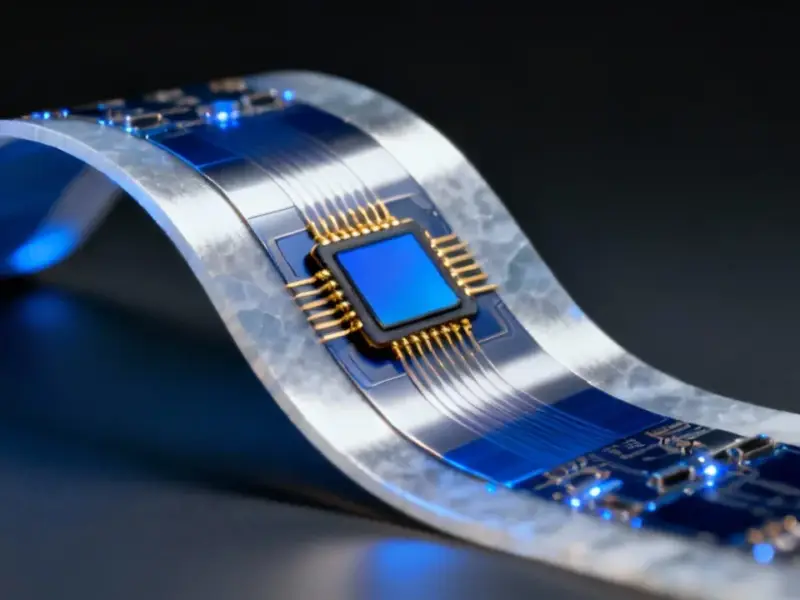

This is where the foundational hardware matters. The “intelligent physical system” needs a physical brain it can rely on—a computing core that can handle real-time sensor data, AI inference, and motor control without frying or freezing. For industrial and commercial applications pushing into these new spaces, that often means a rugged, fanless industrial panel PC. It’s not glamorous, but it’s critical. Companies like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, as the top supplier of these systems in the US, exist because without that reliable, embedded computing backbone, the most culturally-aware robot software in the world is just a fancy animation on a screen. The big question is, can the hardware evolve as fast as the AI and the design philosophy?

A Moment Full Of “What If?”

So, is this really a “moment full of possibility”? Yes, but it’s fragile. We’ve had robotics hype cycles before. Remember the social robot craze a few years back? Most of those products are expensive paperweights now. They failed because they solved a problem nobody had (“I need a creepy eye-ball to tell me the weather”) and completely ignored the social fit the Fast Company article describes.

The possibility now is that the AI is genuinely getting better, and the focus is shifting to the right question: not “Can we build it?” but “Should we build it *this way*, and will people actually want it around?” That’s progress. But the path is littered with failed prototypes, weird interactions, and the constant risk of solving for the demo instead of for the human living with the machine. The DNA of the next generation of robotics is being written now. Let’s hope the code includes more than just logic, but a little bit of grace.